Magnanimous Monikers: Medical Eponyms Named For Patients

While most medical eponyms honor the physician who first (or most prolifically) described the disease, a minority are named for the location of description (e.g., Lyme disease, Warfarin, Nystatin)[1], the causative exposures (e.g., coal miner's lung, Legionnaire’s disease), or for biblical (Job’s syndrome), mythological (Ondine’s curse), or even literary associations (Lady Windermere syndrome, Pickwickian habitus). Some of the most interesting medical eponyms, however, are those named for the patient in whom the disease was described. This is the stories of patients who are remembered with medical eponyms.

HEMATOLOGY

Hematology is replete with examples of patient eponyms. Many of the minor blood group antigens are named for patients (Duffy, Kell, Lewis, Auberger) as well several clotting factors and the associated diseases caused by their deficiencies.

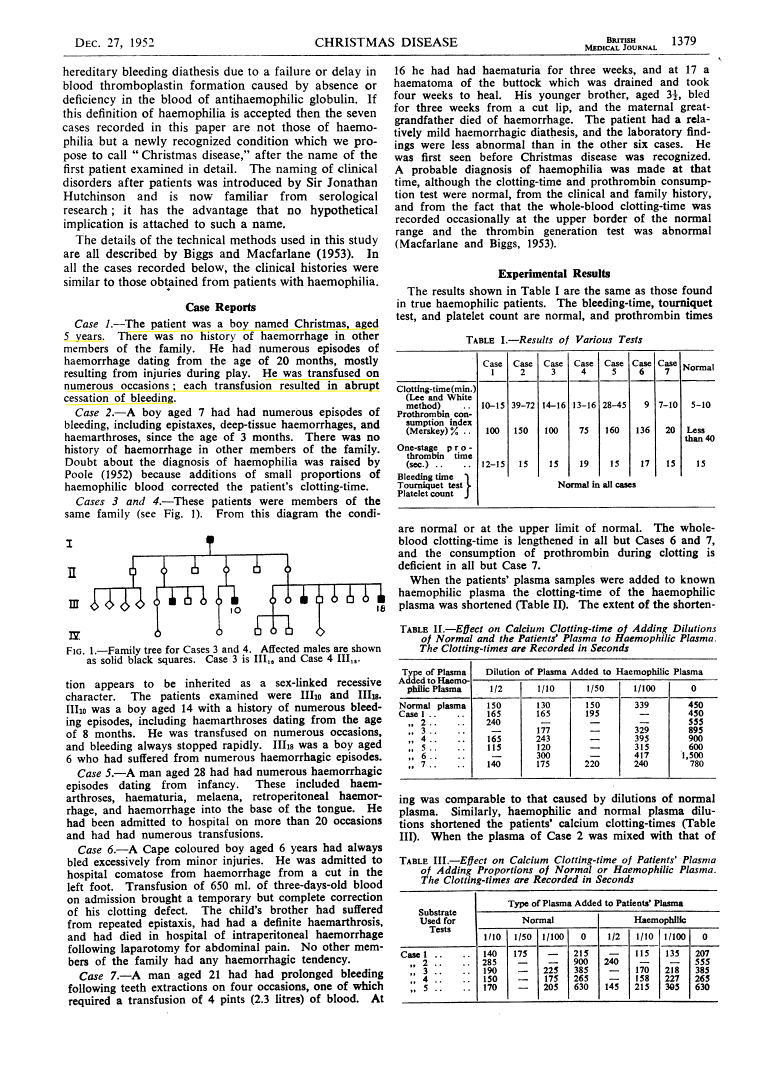

Christmas Disease

The initial description of Hemophilia B in 1952 reported simply: "The patient was a boy named Christmas, aged 5 years." The authors named the disease after him, citing a practice proposed by Sir Jonathan Hutchinson, who somewhat ironically has at least a dozen eponyms after himself.[2] Their paper chronicles Christmas’ story: "He had numerous episodes of hemorrhage dating from the age of 20 months, mostly resulting from injuries during play. He was transfused on numerous occasions; each transfusion resulted in abrupt cessation of bleeding."{1} Surprisingly, his factor VIII levels were normal, and careful analysis of his blood led to the description of a novel form of hemophilia (Hemophilia B) and identification of a new clotting factor (Factor IX) both named for the patient. As an adult, Stephen Christmas continued to receive intermittent transfusions while working as a medical photographer in the same hospital where he had been treated as a child. However, as an unfortunate sequela of his repeated transfusions in the 1980s, he contracted HIV. Christmas became an advocate for transfusion safety and worked to secure compensation for hemophilia patients who, like himself, had contracted HIV from an unscreened blood supply. He died of AIDS in 1993.{2}

Hageman’s Disease

John Hageman was a railway worker who was incidentally noted to have a markedly prolonged PTT on pre-operative labs (without bleeding symptoms), leading to the discovery by Oscar Ratnoff in 1953 of a novel clotting factor, factor XII, and the associated deficiency named for Hageman.{3} Years later, Hageman fractured his pelvis after falling from a boxcar and died of a massive pulmonary embolism after prolonged bedrest.{4,5} Initially, it was speculated that factor XII deficiency could, paradoxically, lead to a hypercoagulable state, though several large epidemiologic studies have failed to show such an association.{6,7} John' Hagemen’s story demonstrates that despite a high PTT, people with Factor XII deficiency are, like anyone else, at risk for thromboembolism, particularly with trauma and venous stasis.

“The Demise of John Hageman” chronicles his death from thromboembolism. NEJM 1968

McLeod syndrome

Hugh McLeod served as a cryptographer in the Army and then attended Harvard dental school. While there, he was incidentally noted to have acanthocytes on a routine blood test. Physical exam disclosed areflexia, and he was found to have an X-linked mutation in the XK gene, one of the Kell blood type antigens, which was described in 1961.{8} Unlike many unfortunate people afflicted by this disease, McLeod went on to have a full life, practicing as a dentist in New Mexico, and eventually succumbing to heart failure, likely as sequela of his eponymous syndrome at age 69.{9}

ONCOLOGY

Troussou’s sign

The French internist Armand Trousseau described the association between gastrointestinal malignancy and migratory thrombophlebitis in the 1860s noting “the frequency with which cancerous patients are affected with painful oedema of the… extremities.” After observing a number of such cases “in which, at autopsy, [he] found visceral cancer”, he described a link between these states that would later be understood as a paraneoplastic phenomenon.{10} Soon after describing his findings, however, Trousseau himself developed thrombophlebitis and told a confidant, “I am lost; a phlegmasia which showed itself… leaves me no doubt about the nature of my affliction.” Indeed, Trousseau had an occult gastric cancer and died later that year.{11,12,13}

Armand Trousseau on his deathbed. Red chalk drawing by G. Dieulafoy, 1867.

HeLa cells

Henrietta Lacks was an African-American woman living in Baltimore who, in 1951, developed an aggressive cervical adenocarcinoma. Before her death, and without her knowledge or consent, her tumor was biopsied and the cells successfully grown in culture.{14,15} This was at the time a momentous scientific advance,{16} and much has been written about the vast contributions to science of Henrietta Lacks’ (HeLa) cells, including new scientific techniques such as cell culture, the Polio vaccine,{17} HIV drugs, and numerous chemotherapeutics. On the other hand, to this day the debate continues regarding the ethics surrounding the collection of Lacks’ cells and the racial and class disparities that may have led investigators to bypass informed consent.{18} Interestingly, HeLa cells have mutated so extensively over decades in culture that debate persists about what constitutes a HeLa cell and whether these cells, each with 70-90 aberrant chromosomes, can still be considered human. Indeed, it was even proposed that HeLa cells, having mutated so extensively, could be thought of as a distinct species. This putative new species, Helacyton gartleri was to be named after both Henrietta Lacks and Stanley Gartner who proposed it.{19} Despite the controversy surrounding the origins or nomenclature of her cells, what is clear is the immense contribution that Henrietta Lacks made to modern medicine.

While HeLa cells are the most well-known and likely most medically significant cell line to be named for the patient from which they are derived, they are actually one of many thousands used daily in laboratories around the world. In 1970, cells derived from Catherine Frances Mallon, a nun in Michigan, lead to identification of the MCF-7[3] cell line{20}, which is ubiquitous in breast cancer research and led to development anti-hormonal therapy to treat breast cancer.{21} Today, thousands of patient-derived cell lines are routinely used in biomedical research. While their provenance is, in some cases, widely known, in most cases their origins are lost to history. It is important to remember that every cell line – and every clinical insight gleaned – emanates directly from a patient’s contribution.

Cowden’s syndrome

In 1963, Lloyd and Dennis described a novel inherited disease that predisposed to cancer: “it shall be referred to as ‘Cowden's disease,’ the family name of the propositus. The clinical findings include: an adenoid facies; hypoplasia of the mandible and maxilla; a high-arch palate; hypoplasia of the soft palate and uvula; microstomia; papillomatosis of the lips and oral pharynx; scrotal tongue; multiple thyroid adenomas.”{22} In addition to these findings, patients present with cancers at a young age, including of the thyroid, breast, and endometrium. The causative mutation was eventually traced to the tumor suppressor PTEN in the late 1990s, and understanding of this pathway has yielded valuable insights about an important biological pathway and its role in many different types of cancer.{23}

GASTROENTEROLOGY

Hartnup Disease

In 1951, a 12-year-old boy, Eddie Hartnup, was admitted to a London hospital. He was originally thought to have pellagra and associated neurological problems, but he failed to improve with vitamin supplementation. Close follow-up and careful family history revealed that several other relatives had a similar phenotype. After a half-decade of work, Baron, Dent, Harris, Hart, and Jepson described in four of eight children in the Hartnup family a "hereditary pellagra-like skin rash with temporary cerebellar ataxia, constant aminoaciduria, and other bizarre biochemical features.” After laboratory evaluation, they deduced the cause as an abnormality of amino acid metabolism.{24,25} Interestingly, Dr. Hart, who had cared for the family for years, rejected naming disease after himself:

At first we described the syndrome among ourselves as “Hart’s syndrome” (despite protests by one of us), and references to it under that name have appeared in papers cited above. Among ourselves we have more recently called it by another very similar name, after the family surname, since alternative names, which describe the main features of the disease – as in the title of this paper – have seemed to us altogether too unmanageable for ordinary usage. We prefer to withhold this name here in case of embarrassment to the family and will refer to it only as “H” disease.{24}

One year later, after obtaining consent from the family{26}, Hart began referring to Hartnup disease.

PSYCHIATRY

Munchaussen’s Syndome

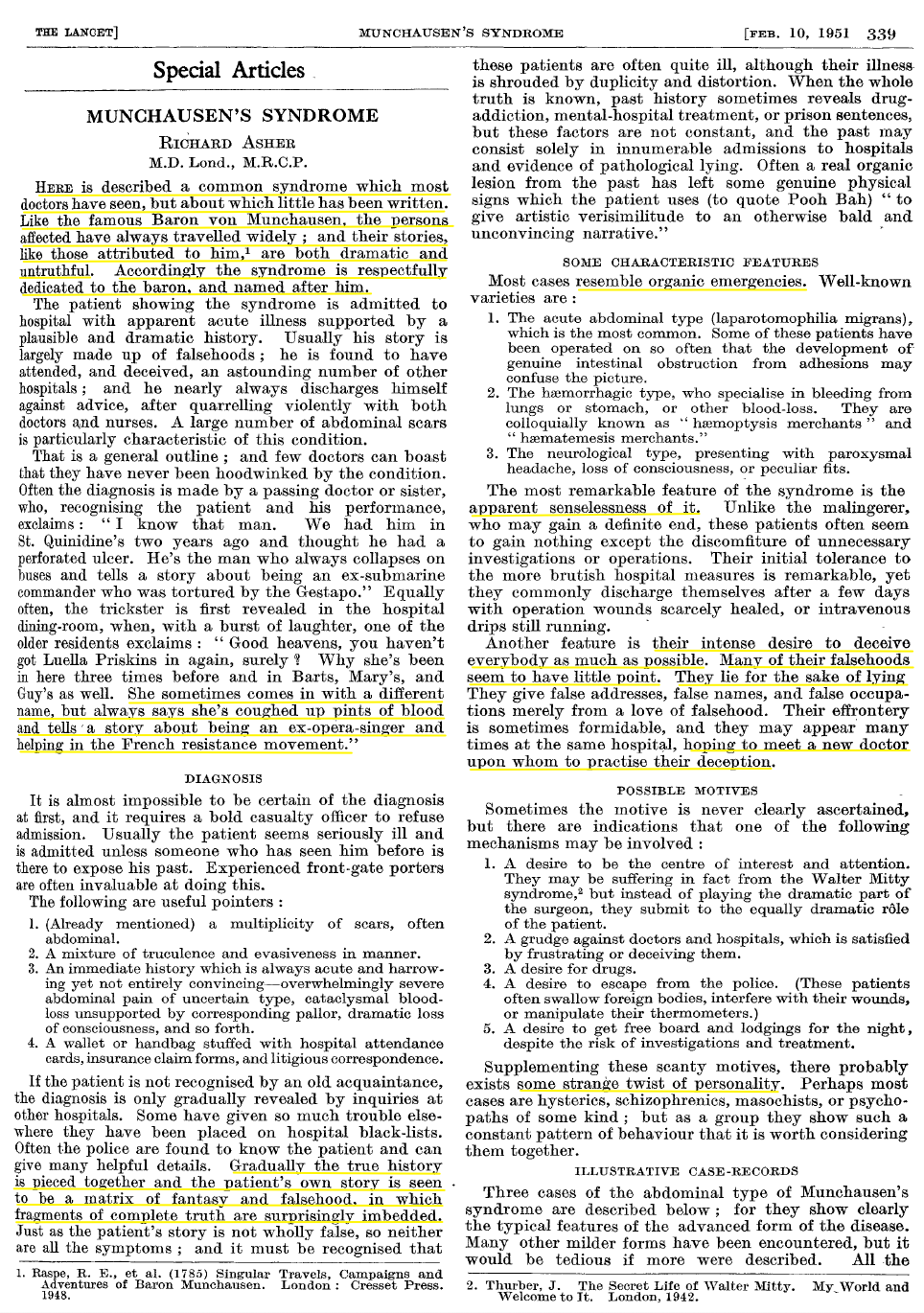

Munchaussen syndrome is named for the German aristocrat Hieronymus Karl Friedrich Freiherr von Münchhausen, a Baron who so exaggerated his adventures in the Russian Cavalry during the Russo-Turkish War that he became a celebrity and inspired Rudolf Erich Raspe to write Baron Munchausen's Narrative of his Marvelous Travels and Campaigns in Russia, a novel about a fictional character (of the same name) with an identical propensity to exaggerate his wartime adventures.[4] The real Baron Münchhausen was so perturbed by his fictional counterpart that he tried, unsuccessfully, to sue the author, who published the book anonymously to escape legal sanction. Had he lived to see it, the real Baron would have likely been incensed when, in 1951, Dr. Richard Asher published a report in the Lancet of a new disease:{27}

Here is described a common syndrome which most doctors have seen, but about which little has been written. Like the famous Baron von Munchausen, the persons affected have always travelled widely; and their stories, like those attributed to him, are both dramatic and untruthful. Accordingly the syndrome is respectfully dedicated to the Baron, and named after him.

Sadly, Baron Münchhausen’s much-admired flair for telling captivating stories has become an ICD-10 code attached quite unflatteringly to a group of peregrinating patients. Subsequently, more variants have been described, including Muchausen’s-by-proxy{28,29} (a caregiver fabricating medical symptoms about a dependent) and Muchausen’s-by-internet (an individual lying about disease to garner online attention).{30}

NEUROLOGY[5]

Lou Gehrig’s Disease

Perhaps the most famous example of a disease known for an afflicted patient is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gerhig's disease. Henry Louis Gehrig was the all star New York Yankees first baseman who played 17 seasons of Major League Baseball and achieved an impressive .340 career batting average, played 2130 consecutive games, and even managed to hit 4 home runs in a single game (a record that still stands). During the 1938 season, however, Gehrig, his teammates, and his fans all noted a decline in his performance, but it was not until summer 1939 that he was formally evaluated by a physician, Dr. Harold Habien of the Mayo Clinic, who vividly recalled making the diagnosis:{34}

When Lou Gehrig entered my office I saw the shuffling gait, his overall expression, then I shook his hand, I knew. I had watched my mother go through the exact same thing. I excused myself from Lou and went straight to Dr. Mayo’s private office. ‘‘Good God,’’ I told him, ‘‘the boy’s got amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)"{35}

Dr. Habien told Gehrig of his diagnosis on his birthday June 19, 1939. One month later on July 4, speaking to a crowd of over 60,000 people at Yankee Stadium, Lou Gerhig delivered the speech that would later be called "The Gettysburg Address of Baseball."

Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about the bad break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of this earth. I have been in ballparks for seventeen years and have never received anything but kindness and encouragement from you fans… So I close in saying that I may have had a bad break, but I have an awful lot to live for.

Following his retirement from baseball, his number (4) was retired – the first time in the history of the sport. Gerhig continued to correspond with his physician, Dr. Patrick O’Leary. His letters chronicled his deterioration but also highlighted his resolve and trust for his doctor. Gerhig survived for 2 years after diagnosis,{36} comparable to the survival today, a testament to Gehrig’s fortitude. Though ALS was well known before Gehrig[6], it assumed a much higher profile after his public disclosure. Gehrig, already a sports hero to millions, became a cause célèbre for ALS, raising awareness (and funding).

Thomsen’s disease

In 1875, the German physician Julius Thomsen described a hereditary myotonia in himself and his family members, painstakingly detailing the clinical features:{37} “after a fright, or in an unexpected joyous movement, this convulsive constriction occurs in all limbs… the victim can not stand upright … The consciousness is, in this case, absolutely indistinct; the sensation of its helplessness is felt very painfully in the eye… This affliction, therefore, has no relation with the epilepsy, which does not occur in the family.”[7] He also describes in detail the pedigree: “There are 36 individuals here, of which only 6 have the same... I myself had had sons; one died young and … betrayed himself the suffering already in the cradle.” He concludes that “I am now myself one of those… with this sad affliction, and the fact of heredity was very clear to me.” Although the autosomal dominant nature of this disease was clearly established by Dr. Thomsen’s keen observations, it would take more than a century for the causative CLCN1 mutations to be identified.

West Syndrome

A worried father and concerned physician, William James West, wrote to the Lancet in 1841 “to call the attention of the medical profession to a very rare and singular species of convulsions peculiar to young children. As the only case I have witnessed is in my own child, I shall be grateful to any member of the medical profession who can give me information on the subject…” He went on to describe the "attacks of emprosthotonos" or "bobbings" he observed of his son James’ head,{38} and lamented that "he neither possesses the intellectual vivacity or the power of moving his limbs, of a child of his age." The father was forced to watch his son's decline, able to document, but not alter his course:

“…for these bobbings increased in frequency, and at length became so frequent and powerful, as to cause a complete heaving of the head forward toward his knees, and then immediately relaxing into the upright position … he never cries at the time of the attacks, or smiles or takes any notice, but looks placid and pitiful”

He attempted all the usual 19th century remedies including “leeches and cold applications to the head, repeated calomel purgatives, and the usual antiphlogistic treatment; the gums were lanced, and the child frequently put into warm baths" as well as administering “syrup of poppies, conium, and opium,” all without success. He sought consultation with experts who were equally powerless.[8]

After Dr. West’s death from dropsy in 1853, James was placed in an asylum for the next 7 years until he too died at age 20. Ultimately the two were buried together in a family grave. West’s syndrome, as infantile spasms are called today, remains enigmatic. While William West’s empiric attempts at treatment failed, his detailed descriptions and scientific approach were valid, and, as contemporary commentators have pointed out, modern empiricism has achieved the treatment he sought:

Dr. West attempted to treat his son’s malady by making assumptions about its etiology and pathophysiology. When this approach failed, he relied on “standard” potions in the medical armamentarium of his day. This might be contrasted with current approaches: efficacy of certain treatments for infantile spasms… ACTH, glucocorticoids, vigabatrin was established empirically. …[M]edical armamentaria change: steroids are commonly used as last-ditch agents today. Had they been available to Dr. West, his son’s spasms might have remitted, and the letter to The Lancet would not have been written.{39}

Surprisingly, between the clinical description by West in 1841 and the EEG characterization in the 1950s, the eponym West syndrome was not used.{39} It was the exhaustive literature review of Henri Gastaut (identifying dozens of names for the disease{40}) that led the scientific community recall the original family once again.

In an 1841 letter to the Lancet, Dr. William West described the onset of “a peculiar form of infantile spasms” in his son James. These spasms would later be called West Syndrome.

Other neurological diseases

Two other rare neurological eponyms are attributed to patients: Machado-Joseph disease (Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 is named after the patriarchs of the two families where it was first described){41} and Troyer Syndrome (a rare autosomal recessive form of spastic paraplegia caused by mutations in the SPG20 gene).{42,43}

OTOLARYNGOLOGY

Louis Armstrong ruptured his orbicularis ori muscle and had to stop playing the trumpet in 1935 until it healed.

Satchmo syndrome

The Great Satchmo, “King of Jazz” Louis Armstrong, who was famous for playing so forcefully that when he recorded, the microphone would have to be moved back several feet, in 1935 sustained a rupture of the orbicularis ori muscle. This injury, eponymously called the “Satchmo Syndrome,” obligated Louis to reluctantly put down his trumpet for the next year.{44}

INFECTIOUS DISEASE

Despite the huge numbers of eponymous microorganisms (Salmonella, Listeria, Brucella, etc), infectious disease seems to be one arena in which physicians are reticent to attach their name. A few viruses, JC and BK virus for example, are named after the initials of afflicted patients. However, several physicians who were themselves patients deserve special mention for going to heroic lengths to prove the association between infection and etiologic agent:

Rickettsiosis

Prior to discovering the bacterial cause of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF), Dr. Howard Taylor Ricketts was famed for his selfless research into endemic fungi. He repeatedly injected himself with blastomycoses “until he became sick enough to realize that this was an experimental procedure not to be repeated.”{45} The intrepid physician next turned his efforts toward RMSF, ultimately identifying the causative organism and proving the connection with disease by injected himself once again. The organism was later named (doubly) in his honor: Rickettsia rickettsii. Unfortunately, he tempted fate one too many times, and in 1909 he died of typhus (Rickettsia prowazakii)[9] while investigating this pathogen in Mexico City.

Schamroth sign

Dr. Leo Schamroth was a South African physician who had repeated bouts of endocarditis and noticed a change in his nail angle.[10] He published this account in an article entitled “Personal Experience” saying, “These are the impressions of a physician at the receiving end of his medical environment… Clinical observation is always a fascinating exercise, and no less so when the observation is directed at oneself.”{46} Somehow, while critically ill and about to undergo emergency surgery to repair his damaged aortic and mitral valves, Schamroth had the presence of mind to describe a new physical examination maneuver to evaluate clubbing.

The recognition of finger clubbing dates back to the original observation of Hippocrates. Yet, early clubbing with 'filling in' of the nail bed is often difficult to evaluate if the finger is viewed in isolation. I found that the assessment of my own clubbing was facilitated by the simple expediency of placing together the dorsal surfaces of the terminal phalanges of similar fingers… In the normal individual, a distinct aperture or 'window', usually diamond-shaped, is formed at the bases of the nail beds. The earliest sign of clubbing is obliteration of this 'window.'

Indeed, Schamroth’s personal observation turned out to be a useful maneuver, and subsequent studies have confirmed the utility of the Schamroth sign in physical diagnosis.{47} Schamroth survived his surgical ordeal and would go on to write over 300 articles and 8 textbooks. He was revered as a teacher and master of electrophysiology. According to one obituary, in diagnosis, he “had the approach of Sherlock Holmes, of whom he was a great fan. He gave the same attention to minute details of apparent irrelevance, often leading to the lucid unraveling of the mystery. He could spot a potential article in a ward case, a clinical presentation, or an ECG, and would stimulate, cajole, and compel junior physicians or even colleagues to write it up. Countless numbers of physicians have benefited from his original ideas, his logical method, and his command of the English language.”{48} One of his books, An Introduction to Electrocardiography, first published in 1957, apparently has the dubious distinction of being the most frequently stolen book from medical libraries.{49}

Leo Schamroth’s 1975 description of a change in nail bed angle seen with clubbing. He observed this on his own fingers while admitted to the hospital with endocarditis.

de Musset’s Sign

Alfred Louis Charles de Musset-Pathay was a 19th century poet, playwright, and author. His works capture the ennui of the post-Napoleonic decline, and he often turned to hedonistic distractions, including a frequent overindulgence in alcohol and a series of dalliances, such as are documented in his autobiographical novel La Confession d'un Enfant du Siècle (The Confession of a Child of the Century). He also had trysts with prostitutes, and his proclivities are manifest in his poem ‘Rolla’ about a destitute young man who contemplates suicide after squandering the last of his fortune on an expensive courtesan. His lifestyle, like many in his time, resulted in syphilis, and in the 1840s, as his literary career peaked, his health declined. He developed worsening vascular disease, including aortitis with aortic insufficiency, manifesting an unusual rhythmic head bobbing due to progressive valvular disease, which his elder brother would vividly recall years later:

During lunch, I observed that the head of my brother was showing a slight bobbing which was involuntary, seemingly occurring with each heartbeat. He asked my mother and me why we were looking at him with such an air of astonishment. We told him what we saw. “I did not think you could see it,” he replied, “but I will reassure you.”

He pressed on his neck, I don’t know exactly how, with his thumb and his index finger and in a moment his head stopped bobbing with each heart beat. “You see,” he said to us, “this dreadful malady is cured by a method which is not only simple but inexpensive as well.”

Mother and I were reassured in our ignorance, not realizing that this was the first sign of a serious affliction which would take his life just fifteen years later…{50}

De Musset (who had previously studied medicine, but given it up because he disliked dissection) was apparently unperturbed by what would become known as his eponymous physical exam finding, but he would ultimately die from heart failure at age 47. While historically memorable, like many of the other physical manifestations of severe aortic regurgitation, his eponymous finding is seldom seen and of uncertain diagnostic utility in modern medicine.{51}

Carrion's disease

In 1885, a Peruvian medical student named Daniel Alcides Carrión García, dramatically inoculated himself with Bartonella bacilliformis. In 1870, when Carrión was 13 years old, an outbreak of “Oroya Fever” struck his hometown killing between 20% and 30% of the people. The desire to understanding this mysterious disease would transfix Carrion, who years later enrolled in medical school. He became interested in two seemingly unrelated diseases, the acute illness known as "Oroya fever" and the chronic diffuse skin rash known as the Peruvian Wart (“veruga peruana”). After seeing both diseases firsthand, Carrion would come to believe they were both manifestations of the same pathogen.

While in his final year of medical school, he asked an intern to inoculate him with the blood of a patient afflicted with the chronic skin disease. Over the following days and weeks he dutifully recorded his symptoms.{52} After 21 days he developed malaise and arthralgias. He would go on to note fevers, hemolytic anemia, and other symptoms that characterized the “Oroya Fever.” As his friends and mentors looked on horrified, he became paler and weaker. After 26 days, he become delirious and asked his friends to continue recording his case history. Forty days after injecting himself he died, but his theory was vindicated. He is now regarded as a Martyr of Peruvian Medicine, and th day of his death, October 5th, is remembered as the Day of Peruvian Medicine.[11] According to a modern account:[12]

Carrión elected the shortest path that was taken by many other exponents of the heroic or romantic medicine of the late nineteenth century in Europe. Inoculations were the shortest route that quickly defined many doubts in the knowledge of morbidity. Carrión had the courage to bet and, unintentionally, lost his life and won the glory.{53}

Carrion’s sacrifice led to the immediate proof of his theory,{54} and the ultimate discovery in 1905 of the species Bartonella – responsible for a slew of human diseases including human Bartonellosis (known as Carrion's disease), Trench fever, Cat scratch disease, and peliosis hepatis. Following the emergence of AIDS, a century after Carrion’s death, another infection related to Bartonella emerged: bacillary angiomatosis, thus more than a century after his death, the knowledge gleaned from Carrion’s self sacrifice remained relevant.

Bacitracin

Drug discovery also occasionally includes attributions to patients. While not strictly speaking a disease, the story of an important and ubiquitous antimicrobial deserves telling. In June of 1943, while playing in the street, 7 year old Tracy was struck by a car sustaining a compound tibial fracture. On admission to the hospital, microscopic exam of fluid from the wound demonstrated Staphylococcus aureus, but the microbiologist Balbina Johnson was surprised to note that by the next morning all trace of the bacteria was absent from culture. Johnson and others were ultimately able to identify the cause, a novel antibiotic derived from a Bacillus subtillis, and in the resulting publication they named the organism (Bacillus subtilis variant Tracy) and the resulting antibiotic after Tracy.{55} Little is know of Tracy, though the antibiotic named for her, Bacitracin, has become a ubiquitous household product.

ORTHOPEDICS

Tommy John Surgery

Tommy John was an all-star pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Tragically in the midst of the 1974 season, he tore his ulnar collateral ligament, an injury that ended his (and de facto the Dodgers’) season and threatened to end his baseball career. Dr. Frank Lobe performed an experimental procedure, the first ulnar collateral ligament repair. Following surgery, Tommy John spent the 1974 season recovering and then went on to win 288 career games (the seventh leading number in baseball history) with more than half of those pitched after his surgery. As of 2014, as many as a third of major league pitchers have undergone the surgery that bears his name.

Jones fracture

Robert Jones was a surgeon who injured himself while dancing and determined the etiology using the nascent field of radiology.[13] He identified others with the same metatarsal fracture over the next months and authored a case series describing the injury:{56}

Some months ago, whilst dancing, I trod on the outer side of my foot, my heel at the moment being off the ground. Something gave way midway down my foot, and I at once suspected a rupture of the peroneus longus tendon. By the help of a friend I managed to walk to my cab, a distance of over 300 or 400 yards. The following morning I carefully examined my foot and discovered that my tendon was intact. There was a slight swelling over the base of the fifth metatarsal bone. I endeavored to obtain crepitus and failed. A finger on the spot gave exquisite pain. Body pressure on the toes, even the slightest, was painful; but when the pressure was deviated to the outer side the pain was still greater. Extension of the ankle and flexion of the toes were immediately felt at the base of the fifth metatarsal. I hobbled down-stairs to my colleague, Dr. David Morgan, and asked him to X-ray my foot. This was done, and the fifth metatarsal was found fractured about three-fourths of an inch from its base.

He described that in all patients with this fracture, himself included, the clinical exam and radiographic findings were identical.

CONCLUSION

Despite their ubiquity in the medical patois, many controversies persist surrounding medical eponyms ranging from the linguistic (when should an apostrophe be used? For example Down’s versus Downs syndrome){57}, to the ethical (is it appropriate to honor physicians of dubious character, with names such as Wegner’s Granulomosis){58}, to the practical (are eponyms easier to remember than descriptive names?) and even existential (should we be using eponyms at all?).{59}

Patient-eponyms are a unique and important, albeit small, subset of the vast medical lexicon. While it is important to recognize the contributions of physicians in advancing medicine, we should remember that this progress is only possible with the help of our patients. Working at a time that both embraces HIPAA-mandated medical privacy and therefore shuns the use of eponyms, it is easy to forget the contributions of individual patients to the cause of advancing medical understanding and improving treatment. At the same time, with the vast medical literature now widely accessible, searchable, and open access, is it still an “honor” to publicize our patients’ illnesses? While there are likely to be few new diseases named for patients in the foreseeable future, it is important to remember those eponyms that we already have.

A summary of medical eponyms named for patients

| Eponym | Named For | Described By | Year | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacitracin | "Tracy L" (dates unknown) |

BA Johnson, H Anker, & FL Meleney | 1945 | 55 |

| Carrion’s disease (Bartonellosis) |

Daniel Alcides Carrión García (1857 – 1885) |

himself | 1885 | 54 |

| Christmas disease (Factor IX deficiency) |

Stephen Christmas (1947 – 1993) |

1952 | 1 | |

| Cowden’s syndrome (PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome) |

The Cowden Family | KM Lloyd & M Dennis | 1963 | 22 |

| de Musset’s sign (Aortic insufficiency) |

Alfred Louis Charles de Musset-Pathay (1810 - 1857) |

A Delpeuch | 1900 | 50 |

| Hageman disease (Factor XII deficiency) |

John Hageman(1920 – 1968) | Oscar Ratnoff, Jane Colopy | 1953 | 3 |

| Hartnup disease (Neutral 1 amino acid transport defect) |

Eddie Hartnup and his family | Baron et al | 1956 | 24 |

| HeLa Cells | Henrietta Lacks (1920 – 1951) |

George Grey | 1951 | 16 |

| JC Virus | John Cunningham (dates unknown) |

Zurhein and Chou | 1965 | 61 |

| Jones fracture (fifth metatarsal fracture) |

Robert Jones (1857 – 1933) |

himself | 1902 | 56 |

| Lou Gehrig’s disease (Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) |

Lou Gehrig (1903 – 1941) |

Jean-Martin Charcot | 1869 | |

| Machado-Joseph disease (Spinocerebellar ataxia 3) |

William Machado and Antone Joseph | KK Nakano, DM Dawson, A Spence | 1972 | 41 |

| McLeod Syndrome (x-linked neuroacanthosis) |

Hugh McLeod (1936 - 2004) |

FH Allen, SM Krabbe, PA Corcoran | 1961 | 8 |

| Munchausen syndrome (Factious disorder) |

Hieronymus Karl Friedrich, Freiherr von Münchhausen (1720-1797) |

Richard Asher | 1951 | 27 |

| Rickettsia | Howard Taylor Ricketts (1871 – 1910) |

himself | 1906 | |

| Satchmo Syndrome (rupture of Orbicularis oris muscle) |

Louis Armstrong (1901 – 1971) |

1935 | ||

| Schamroth Sign (digital clubbing) |

Leo Schamroth (1924 – 1988) |

himself | 1976 | 46 |

| Thomsen’s disease (Myotonia congentia) |

Julius Thomsen and his family | himself | 1875 | 37 |

| Troussou’s Sign (migratory thromboplebitis) |

Armand Troussou (1801 – 1867) |

himself | 1860 | 10 |

| Troyer Syndrome (hereditary spastic paraplegia) |

Troyer family | Adolf Seeligmüller | 1876 | 42 |

| West Syndrome (Infantile Myoclonic Encephalopathy) |

James Edwin West (1840–1860) |

William James West | 1841 | 38 |

Footnotes

[1] Diseases named for places, or toponyms, often have interesting back stories. In 1940, dicoumarol was discovered in spoiled hay that had caused hemorrhagic illness among cattle. The discovery was made at the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, so the resulting drug was called WARFarin. Similarly, Elizabeth Hazen and Rachel Brown discovered a potent antifungal compound produced by a Streptomyces noursei (which was first isolated from a neighbor’s garden) in New York State, which they termed NYSTATin.

[2] Jonathan Hutchinson (opthalmologist, dermatologist, surgeon, internist, and pathologist) did name many diseases after patients, though few persist in modern usage. These include Mabey Malady, Branford Legs, and Mortimer’s disease, the latter of which is characterized by diffuse symmetric erythematous skin patches due to non-caseating granulomas. We would now probably refer to this as sarcoidosis, though some debate exists about whether Mortimer’s disease is really the first report of it.

See Pandhi D, Sonthalia S, Singal A. Mortimer's Malady revisited: a case of polymorphic cutaneous and systemic sarcoidosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010 Jul-Aug;76(4):448. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.66606.

[3] Note that MCF-7 refers to Michigan Cancer Foundation, not the patient’s initials. Part of what makes HeLa cells so unusual is that the name of the cell line actually reflects the name of the patient.

[4] The exploits of the fictional Münchhausen (whose name was Anglicized to Munchausen) were somewhat more grandiose than his real-world counterpart and included fighting a 40-foot crocodile, riding a cannonball, and journeying to the moon by way of a hot air balloon.

[5] Some accounts erroneously report that Dr. George Huntington described the eponymous disease in himself and his own family. None of the Huntington’s had Huntington’s disease. In fact, George Huntington drew upon the case histories and experience of his father (Dr. George Lee Huntington) and Grandfather (Dr. Abel Huntington) to definitively establish the pedigree of the disease in another family that the Huntingtons’ had cared for over three generations in East Hampton, NY.

[6] Jean-Martin Charcot and colleagues at the Hospital de la Salpêtrière deserve credit for the clinical and pathological description of ALS in seminal work done between 1865 and 1869. The name “amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” was coined by Charcot later in 1874. Outside of the US, ALS is typically called “Charcot’s disease.”

[7] These are based on my (Google Translate assisted) translations of excerpts of Thomsen’s manuscript, which has to my knowledge never been translated into English.

[8] Worth noting that although West was the first to describe infantile spasms in the medical literature, other physicians, including those with whom West consulted, knew the condition as “Salaam Convulsions” in reference to the customary Arabic deep bow on greeting.

[9] Rickett’s colleague, Stanislav von Prowazek, also died of typhus while investigating it in Mexico.

[10] Schamroth had much to add to the medical literature with his wit and wisdom. His article “Personal Experience” should be required reading for any student of physical exam, medical humanities, or who simply appreciates a good rant about the quality of hospital food.

[11] Self-experimentation has claimed the lives of more than a few physicians interested in infectious disease. Jesse William Lazear died in 1900 in Cuba after allowing a mosquito infected with Yellow Fever to bite him, thus proving how the virus was transmitted.

For an excellent discussion of the heroic/foolhardy history of self-experimentation in medicine, see Lawrence K. Altman, Who Goes First?: The Story of Self-experimentation in Medicine, pp. 149-150, University of California Press, 1987

[12] Translation is mine. Original text: “Carrión eligió el camino más corto al igual que muchos otros exponentes de la medicina heroica o romántica de fines del siglo XIX que fenecía en Europa. Las inoculaciones eran el camino más corto que definía rápidamente muchas dudas en el conocimiento de los morbos. Carrión tuvo el coraje de apostar y, sin quererlo, perdió la vida y ganó la Gloria.”

[13] Jones would today be termed an “early adopter” of radiology. On February 7, 1896 – just weeks after Wilhelm Röntgen demonstrated the existence of X-rays on December 28, 1895 – Jones and a colleague use an X-ray machine to find a bullet lodged in a 12 year old boy’s wrist. This report was published in the Lancet as the first clinical radiograph.

Jones R; Lodge O. (22 February 1896). "The discovery of a bullet lost in the wrist by means of the Roentgen rays.". Lancet. 147 (3782): 476–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)93204-0

REFERENCES

1. Biggs R, Douglas AS, Macfarlane RG, Dacie JV, Pitney WR, Merskey. Christmas disease: a condition previously mistaken for haemophilia. Br Med J 1952; 2(4799): 1378-1382.

2. Giangrande PL. Six characters in search of an author: the history of the nomenclature of coagulation factors. Br J Haematol 2003; 121(5): 703-712.

3. Ratnoff OD, Margolius A, Jr. Hageman trait: an asymptomatic disorder of blood coagulation. Trans Assoc Am Physicians 1955; 68: 149-154.

4. Ratnoff OD, Busse RJJ, Sheon RP. The Demise of John Hageman. New England Journal of Medicine 1968; 279(14): 760-761.

5. Renne T, Schmaier AH, Nickel KF, Blomback M, Maas C. In vivo roles of factor XII. Blood 2012; 120(22): 4296-4303.

6. Zeerleder S, Schloesser M, Redondo M, Wuillemin WA, Engel W, Furlan M, et al. Reevaluation of the incidence of thromboembolic complications in congenital factor XII deficiency--a study on 73 subjects from 14 Swiss families. Thromb Haemost 1999; 82(4): 1240-1246.

7. Koster T, Rosendaal FR, Briet E, Vandenbroucke JP. John Hageman's factor and deep-vein thrombosis: Leiden thrombophilia Study. Br J Haematol 1994; 87(2): 422-424.

8. Allen FH, Jr., Krabbe SM, Corcoran PA. A new phenotype (McLeod) in the Kell blood-group system. Vox Sang 1961; 6: 555-560.

9. Hewer E, Danek A, Schoser BG, Miranda M, Reichard R, Castiglioni C, et al. McLeod myopathy revisited: more neurogenic and less benign. Brain 2007; 130(Pt 12): 3285-3296.

10. Trousseau A. Phlegmasia alba dolens (lecture XCV). Lindsay & Blakiston: Philadelphia, 1873.

11. Samuels MA, King ME, Balis U. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 31-2002. A 61-year-old man with headache and multiple infarcts. N Engl J Med 2002; 347(15): 1187-1194.

12. Aron E. [The 100th anniversary of the death of A. Trousseau]. Presse Med 1967; 75(27): 1429-1430.

13. Soubiran A. ["Is he king of some island?" or the last Christman of Trousseau]. Presse Med 1967; 75(54): 2807-2810.

14. Smith V. Wonder Woman: The Life, Death, and Life After Death of Henrietta Lacks, Unwitting Heroine of Modern Medical Science. Baltimore City Paper 2001.

15. Skloot R. The immortal life of Henrietta Lacks. Crown Publishers: New York, 2010, x, 369 p., 368 p. of platespp.

16. Gey GO, Coffman, W. D. & Kubicek, M. T. Tissue culture studies of the proliferative capacity of cervical carcinoma and normal epithelium. Cancer Res 1952; 12: 264-265.

17. Salk JE. Considerations in the preparation and use of poliomyelitis virus vaccine. J Am Med Assoc 1955; 158: 1239-1248.

18. Skloot R. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. Broadway Books: New York, NY, USA, 2011, 381pp.

19. Val Valen LMM, V. C. HeLa, a new microbial species. Evolutionary Theory 1991; 10: 71-74.

20. Soule HD, Vazguez J, Long A, Albert S, Brennan M. A human cell line from a pleural effusion derived from a breast carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 1973; 51(5): 1409-1416.

21. Comsa S, Cimpean AM, Raica M. The Story of MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cell Line: 40 years of Experience in Research. Anticancer Res 2015; 35(6): 3147-3154.

22. Lloyd KM, 2nd, Dennis M. Cowden's disease. A possible new symptom complex with multiple system involvement. Ann Intern Med 1963; 58: 136-142.

23. Liaw D, Marsh DJ, Li J, Dahia PL, Wang SI, Zheng Z, et al. Germline mutations of the PTEN gene in Cowden disease, an inherited breast and thyroid cancer syndrome. Nat Genet 1997; 16(1): 64-67.

24. Baron DN, Dent CE, Harris H, Hart EW, Jepson JB. Hereditary pellagra-like skin rash with temporary cerebellar ataxia, constant renal amino-aciduria, and other bizarre biochemical features. Lancet 1956; 271(6940): 421-428.

25. Harris H. Renal aminoaciduria. Br Med Bull 1957; 13(1): 26-28.

26. Association BP. Proceedings of the Twenty-eighth Annual General Meeting Arch Dis Child 1957; 32(164): 361-366.

27. Asher R. Munchausen's syndrome. Lancet 1951; 1(6650): 339-341.

28. Meadow R. Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The hinterland of child abuse. Lancet 1977; 2(8033): 343-345.

29. Money J, Werlwas J. Folie a deux in the parents of psychosocial dwarfs: two cases. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1976; 4(4): 351-362.

30. Feldman MD. Munchausen by Internet: detecting factitious illness and crisis on the Internet. South Med J 2000; 93(7): 669-672.

31. Magherini G. La Sindrome di Stendhal: Milan, 1992.

32. Stendhal Md. Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio. 1817.

33. Courbon P FG. Syndrome d'illusion Fregoli et schizophrenie. Bulletin de la Societé Clinique de Medicine Mentale 1927; 15: 121-124.

34. Brennan F. The 70th anniversary of the death of Lou Gehrig. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012; 29(7): 512-514.

35. R B. Lou Gehrig: An American Classic. Taylor Publishing: Dallas, TX, 1995.

36. GEHRIG, 'IRON MAN' OF BASEBALL, DIES AT THE AGE OF 37; Rare Disease Forced Famous Batter to Retire in 1939 -- Played 2,130 Games in Row SET MANY HITTING MARKS Native of New York, He Became Star of Yankees -- Idol of Fans Throughout Nation GEHRIG, 'IRON MAN' OF BASEBALL, DIES GEHRIG AS A PLAYER AND AFTER HE RETIRED FROM BASEBALL. New York Times. 1941 June 3.

37. Thomsen J. Tonische Krämpfe in willkürlich beweglichen Muskeln in Folge von ererbter physischer Disposition. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 1875; 6: 702-817.

38. West W. On a Peculiar Form of Infantile Convulsions. The Lancet 1841; 35(911): 724.

39. Eling P, Renier WO, Pomper J, Baram TZ. The mystery of the Doctor's son, or the riddle of West syndrome. Neurology 2002; 58(6): 953-955.

40. Fukuyama Y. History of clinical identification of West syndrome--in quest after the classic. Brain Dev 2001; 23(8): 779-787.

41. Nakano KK, Dawson DM, Spence A. Machado disease. A hereditary ataxia in Portuguese emigrants to Massachusetts. Neurology 1972; 22(1): 49-55.

42. Seeligmüller A. Einige seltenere Formen von Affectonen des Rückenmarks: I. Sklerose der Seintenstränge des Rückenmarks bei vier Kindern derselben Familie Deutsch Med Wschr 1876; 2: 185-186.

43. Cross HE, McKusick VA. The Troyer syndrome. A recessive form of spastic paraplegia with distal muscle wasting. Arch Neurol 1967; 16(5): 473-485.

44. Planas J. Rupture of the orbicularis oris in trumpet players (Satchmo's syndrome). Plast Reconstr Surg 1982; 69(4): 690-693.

45. Weiss E, Strauss BS. The life and career of Howard Taylor Ricketts. Rev Infect Dis 1991; 13(6): 1241-1242.

46. Schamroth L. Personal experience. S Afr Med J 1976; 50(9): 297-300.

47. Pallares-Sanmartin A, Leiro-Fernandez V, Cebreiro TL, Botana-Rial M, Fernandez-Villar A. Validity and reliability of the Schamroth sign for the diagnosis of clubbing. JAMA 2010; 304(2): 159-161.

48. Barold SS. Biography of Leo Schamroth. 2009 [cited; Available via the Internet Wayback Machine]. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20090105182312/http://www.hrsonline.org/News/ep-history/notable-figures/leoschamroth.cfm

49. Wikipedia: Leo Schamroth. [cited 2017; Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leo_Schamroth

50. Delpeuch A. Le signe de Musset. Secousses rythmées de la tête chez les aortiques. Presse Med 1900; 8: 237-238.

51. Sapira JD. Quincke, de Musset, Duroziez, and Hill: some aortic regurgitations. South Med J 1981; 74(4): 459-467.

52. Cueto M. Tropical medicine and bacteriology in Boston and Peru: studies of Carrion's disease in the early twentieth century. Med Hist 1996; 40(3): 344-364.

53. Pamo Reyna O. Carrión: mito y realidad. Revista Medica Herediana 2003.

54. Odriozola E. La erupción en la infermadad de Carrión (verruga peruviana). El monitor médico 1895; 10: 309-311.

55. Johnson BA, Anker H, Meleney FL. Bacitracin: A New Antibiotic Produced by a Member of the B. Subtilis Group. Science 1945; 102(2650): 376-377.

56. Jones R. I. Fracture of the Base of the Fifth Metatarsal Bone by Indirect Violence. Ann Surg 1902; 35(6): 697-700 692.

57. Akhter M. The apostrophe in medical eponyms. Int J Cardiol 2013; 166(2): 529.

58. Falk RJ, Gross WL, Guillevin L, Hoffman GS, Jayne DR, Jennette JC, et al. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's): an alternative name for Wegener's granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63(4): 863-864.

59. T C. The Status of Medical Eponyms: advantages and disadvantages. In: Loiacono A IG, Grego K (ed). Teaching Medical English: Methods and Models. Polimetrica International Scientific: Monza, Italy, 2011.

60. Gardner SD, Field AM, Coleman DV, Hulme B. New human papovavirus (B.K.) isolated from urine after renal transplantation. Lancet 1971; 1(7712): 1253-1257.

61. Zurhein G, Chou SM. Particles Resembling Papova Viruses in Human Cerebral Demyelinating Disease. Science 1965; 148(3676): 1477-1479.