Spherical Sanitarium: What can a 900 ton steel sphere teach us about bad medicine

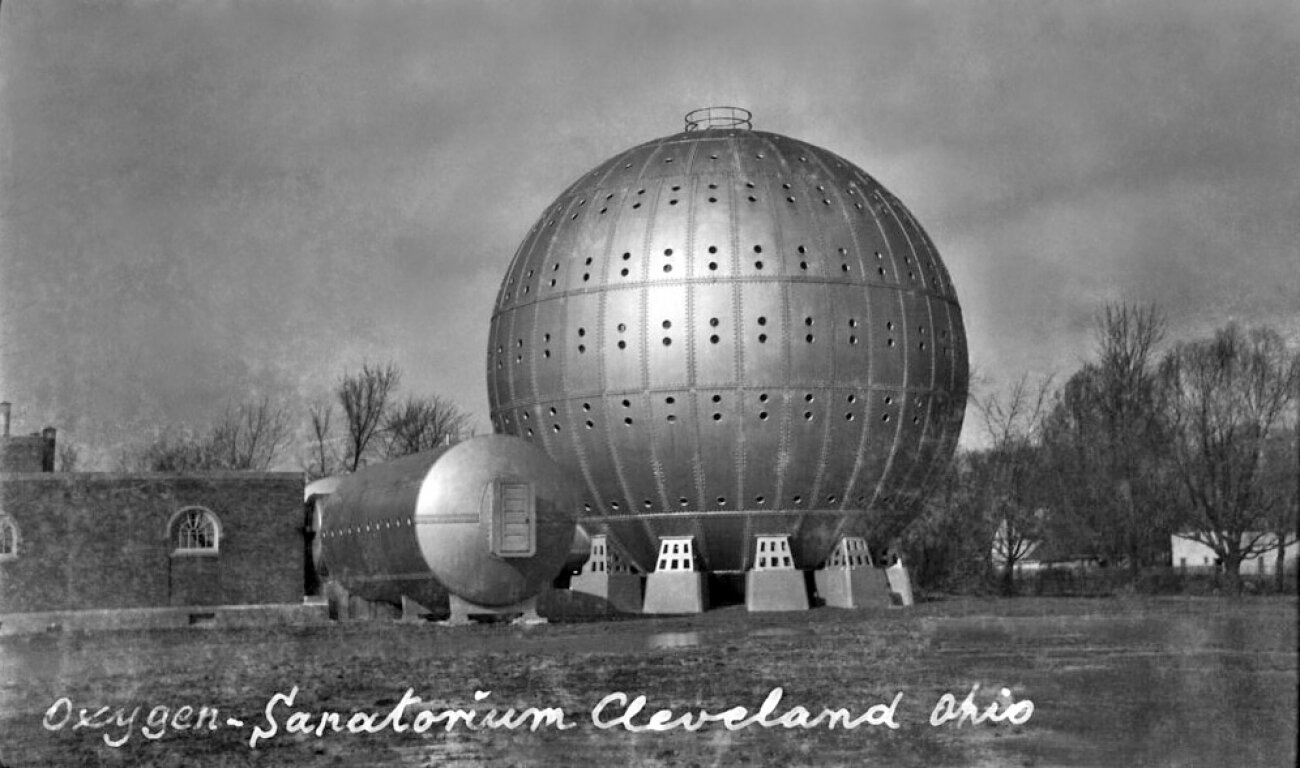

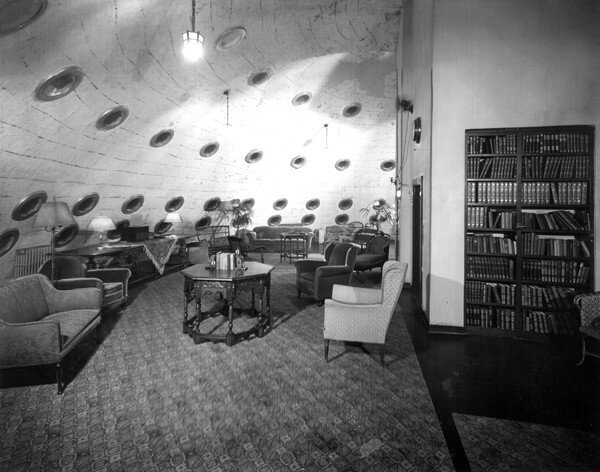

In 1928, the residents of Cleveland, Ohio watched in wonder as a unique structure was erected along the shores of Lake Erie. Over months a huge steel ball took shape, some 64 feet in diameter containing five stories. When it was completed it held 38 rooms, 350 portholes to provide natural light, an elevator, and an ornate recreation room replete with crystal chandeliers. This strange spherical building was the first - and only - of its kind in the world: a hospital pressurized to 60 PSI that promised a panacea for its patients, able to cure a broad range of ailments ranging from diabetes to pernicious anemia to cancer. This was Dr. Orval Cunningham's Sanatorium, or “Timken's Tank,” after its benefactor, the “Baron of bearings” tycoon Henry H. Timken who bankrolled the $1,000,000 to build it. This unusual sphere was both an early hyperbaric hospital and a 900 ton monument to the dangers of unscientific medicine.

The monstrous steel ball was the pinnacle of over a decade of work by Cunningham, but the idea of hyperbarics was much older. The first chamber intended to increase atmospheric pressure had been built by the British physician Nathanial Henshaw in the 1660s and was allegedly able to cure consumption, asthma, and a slew of other maladies. In 1834, Junod and Fabare built a copper sphere, which could be pressurized to 4 atmospheres and was used to treat pulmonary diseases. In the 1880s, while constructing the Brooklyn Bridge, over 100 workers fell ill with a crippling “Caisson Disease” named for the high pressure underwater chambers they worked in to excavate the foundation of the bridge. In 1908, JS Haldane identified the etiology of decompression sickness, or “the Bends,” named for the crippling joint and back pain it caused in Caisson workers, and developed the first treatment for it using compression chambers.

Dr. Orval Cunningham, chairman of the department of anesthesia at Kansas University Medical School, came on the hyperbaric scene in 1918 after witnessing the effects of atmospheric pressure during the Great Influenza Pandemic. He observed the people who moved from Denver to Kansas city appeared to improve, reasoning that the increased atmospheric pressure must be beneficial. He posited that the denser air had a salubrious and antimicrobial effect.

He built his first hyperbaric chamber next to his clinic - an 8 foot by 30 foot tube - and treated dozens suffering from influenza or pneumonia. Nothing is published about this work, but it is possible that these early experiments were truly beneficial to patients; hyperbaric air really could deliver more oxygen, which is potentially life saving for a hypoxic patient suffering from pneumonia. Over the next few years, Cunningham dedicated more and more of his time to hyperbarics. As he constructed a series of larger chambers, his claims about the benefits of “tank treatments” became more expansive. He theorized that many diseases - including diabetes and cancer - were caused by as yet undiscovered anaerobic microorganisms that were unable to grow in the presence of oxygen. Thus he reasoned that high pressure air could be a panacea for many diseases for a price.

During his time in Kansas City, Cunningham treated a prominent industrialist, Henry H. Timken Jr., for uremia inside his pressure chamber. Timken’s father, Henry Timken Sr., had made his fortune pioneering the manufacture of crucial components of an increasingly mechanized society, first an improved carriage spring for horse drawn buggies, then a superior roller bearing that earned him millions and the monikers the “Baron of Bearings" or “The King of Ball Bearings.” His heir, HH Timken Jr., was greatly impressed by the experience in his hyperbaric “tanks” and offered to help Cunningham scale up his enterprise. The true cause of Timken’s ailment is unknown, though it’s possible that Cunningham’s tanks inadvertently treated his uremia through Charles’ law: by increasing the pressure, he also increased the temperature. Since the time of ancient Rome, it was known that sweating could remove uremic toxins. Thus it’s possible that a transient cause of uremia was treated by hyperbarics, albeit due to a side effect of pressurization, not the pressure itself. Whatever the reason - Timken considered himself cured and dedicated substantial resources to seeing Cunningham’s hyperbaric dreams realized. A million dollar investment (the equivalent of $15m today) and the assistance of Timken’s engineers was enough to scale up Cunningham’s hospital and build the immense “Timken Tank” in Cleveland.

But as Cunningham’s fame was rising, the medical profession was growing skeptical. The American Medical Association began investigating some of these more dubious claims in 1921. They identified many cases of desperate patients and families being offered a cure, if they could pay for it. For example they learned that Dr. Cunningham advised the parents of a sixteen-year old girl with diabetes mellitus that he "had cured many cases of diabetes and cancer with his treatment and that he would give her treatments for $306 a month [$4,424 a month today]. This girl's parents are very poor but they have decided to raise the money to send her to the 'sanitarium' of Dr. Cunningham, so that she would not have to take insulin anymore.”

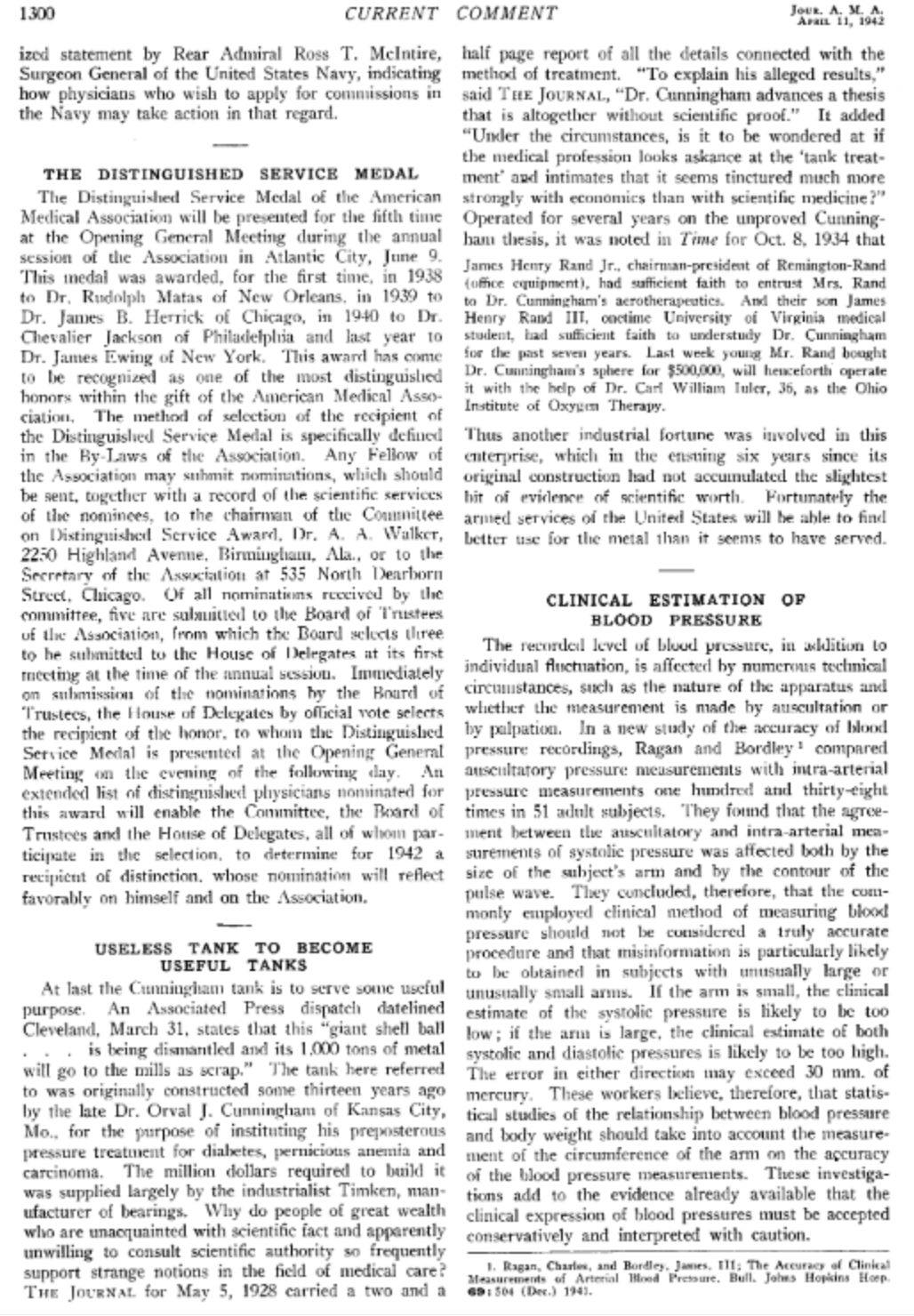

The AMA investigated his finances, concluding that he was likely earning over a hundred thousand dollars per year (the equivalent of $1.4 million today) by offering “tank treatments.” He may have also sold stock and licensed his patents, potentially extracting hundreds of thousands to millions more. The AMA invited Cunningham to publish his results or answer questions in writing. He was evasive. Finally, after seven months of delays, he reiterated his claims that his tanks could cure cure syphilis, diabetes, arthritis, and pernicious anemia. No evidence to support these claims was ever provided.

Cunningham’s Lakeside Sanitarium opened in 1928 but within a few years was struggling. The combination of the Great Depression and a scathing JAMA article critiquing his unscientific methods may have doomed his once thriving hyperbaric business. In 1934 he sold his Spherical Sanitarium to his wealthy protege, James Rand Jr., for $500,000, and it was renamed the Ohio Institute of Oxygen Therapy. Despite a change in name and ownership, the hospital remained unprofitable and was sold again in 1936. The new owners were once again unable to turn a profit, and the hospital closed its doors for good in 1938.

Cunningham suffered a stroke and died in February 1937. The Ohio Institute for Oxygen Therapy was charged with violating Ohio Security laws in September and ultimately dissolved. The hospital was abandoned and fell into disuse. In 1940 the Cleveland diocese purchases the lakefront land and its odd spherical building to use as a summer camp, but the war interceded. Ultimately the hospital was torn down in 1942, its now rusting 1/2 inch steel plate repurposed as war material.

A JAMA articles in 1942, entitled “Useless tank to become useful tanks” eulogized the structure concluding that it “advance[d] a thesis that is altogether without scientific proof” adding that it is no wonder that "the medical profession looks askance at the 'tank treatment' and intimates that it seems tinctured much more strongly with economics than with scientific medicine.” It concluded, "Fortunately, the armed services of the United States will be able to find better use for the metal...”

Over the last century, hyperbaric medicine has become legitimate evidence based specialty, but much of the atmosphere surrounding Cunningham’s work remains unchanged. Beginning in 2003, a California company called “Real-time cures" raised over $700 million from investors, promising that its miraculous blood testing would revolutionize medicine. That company later changed its name to Theranos and ceased operations in 2018 after numerous investigations revealed that its technology was fraudulent. As JAMA wondered about Timken in 1942, it is reasonable today to ask why "people of great wealth who are unacquainted with scientific fact and apparently unwilling to consult scientific authority so frequently support strange notions in the filed of medical care.”

One of the challenges of debunking Cunningham’s claims was that it contained a nucleus of truth - hyperbarics really did help Caisson workers and possibly a few others. We see something similar today with the proliferation of rogue stem cell clinics in the US. Between 2009 and 2014 the number of clinics offering to inject stem cells roughly doubled each year, reaching over 700 by 2017. There are truly life saving therapies based on stem cells - bone marrow transplant for one - but these clinics, with their dubious non-evidence based claims about curing all manner of disease, do not offer them.

Recently we have also seen several prominent examples of of pseudo-scientific cures in medicine: the “metabolic cure for sepsis” (vitamin C), hydroxychloroquine for COVID19, among others. Although both seemed promising initially, both have been largely debunked, yet like Cunningham’s “tank treatments”, their proponents continue to promulgate them. In 1942, TIME magazine wrote that Cunningham may have been "perfectly sincere and honest in his belief that he had stumbled on something. As is always the case, however, when some new method of treating human beings is carried out without any independent check or balances, there seems little doubt that Dr. Cunningham has allowed his subject to run away with him.”

The temptation to profit from desperate patients with incurable disease by peddling cures based on the newest technology persists today just as when Cunningham’s tanks were built in the 1920s, and reputational enhancement can be just as insidious a motivator as wealth. Snake oil comes in many formulations - stem cells, vitamin C, hydroxychloroquine, and compression tanks - but the solution to all is the same: demanding transparent and accountable release of data for peer review and rigorous dispassionate testing of novel treatments.

Nothing remains of Cunningham’s steel edifice today. His 900 ton spherical hospital - still the largest hyperbaric chamber ever built - is noted in textbooks as an early and misguided milestone in hyperbaric medicine. Though the structure was scrapped long ago, Cunningham’s sphere endures, figuratively at least, as a monument to medicine that far exceeded its evidence base.